Studies of manure application reveal antibiotic resistance movement

Studies of manure application reveal antibiotic resistance movement

While using manure as an organic source of fertilizer has helped the agricultural industry maintain balance in integrated crop and livestock systems, there is some risk the manure contains bacteria that may contaminate water bodies if transported off the field by rain.

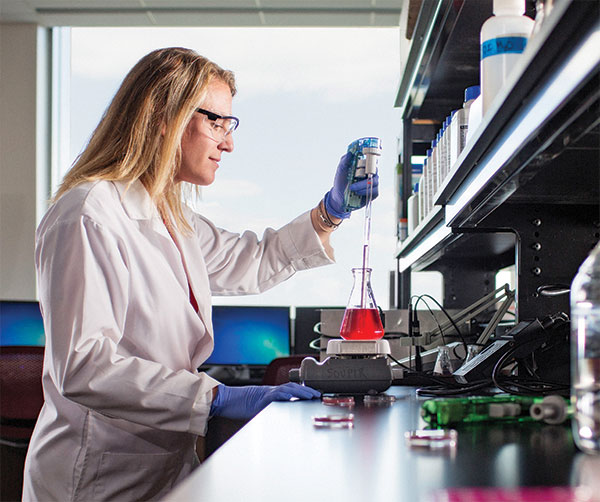

Michelle Soupir, an associate professor in the Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering, and her team of researchers are examining the transport of two pathogen indicators: E. coli and enterococci. Both are identified by the EPA as indicators of potential fecal contamination of water resources. She also looks for relationships between the traditional pathogen indicators and antibiotic resistance.

Soupir says identifying the resistance is incredibly difficult. “When you monitor environmental systems, you can be on a fishing trip of sorts when determining what resistance might be out in the environment. In our study, we targeted tetracycline and tylosin.” Both are antibiotics. Tetracycline treats bacterial infections like acne and genital or urinary infections, whereas tylosin isn’t prescribed to humans but is in the same class as other common human antibiotics like erythromycin.

The fieldwork is conducted at the North East Iowa Research Farm (NERF), near Nashua, Iowa. A different land-use treatment is applied to one-acre plots of crops, separated from other plots by berms and curtain drains to reduce cross-contamination from either above or below the surface. Manure is injected into some of the plots in bands close to the root system before the first hard frost.

“It’s applied in the fall so ammonia doesn’t volatilize, and we don’t lose the nitrogen we’re applying,” says Soupir. “It’s always a gamble, because you want to do it right before the soil freezes.” The manure is then held in the soil all winter at cold temperatures, which is a benefit to water quality as the cold temperatures tend to kill off some of the pathogens and resistant bacteria.

The team is getting data from three points in the system. Samples of the manure that is applied to specific plots tells them how much antibiotic resistant bacteria and pathogen indicators are going onto the plots. Measurements of the soil show how long the organisms survive. This leads the research team to take samples of water, which tells them what organisms are moving off site and could potentially be moving into surface water.

But the results of this have not been as expected. “We rarely see statistically significant differences between the manure amended and control plots in the tile drainage water,” says Soupir. “It’s been surprising that there aren’t more statistical differences. For the most part, it’s been pretty good news for pork producers because the method of manure application (injection in the fall) seems to be a good management strategy for preventing pathogens and resistant bacteria from moving into the tile drains.”

The project is on its fourth year, and while most of the results are on swine manure, the researchers have begun to look at a poultry-amended site as well as a beef-amended site. Soupir says these research sites are novel because they have received manure application for long periods of time. “It’s really made me appreciate the need for long-term studies.”